Hello after many months! I am not good at setting deadlines for myself. I know this, I am working on this, and I think the right people will overlook this enduring (and endearing?) personal shortcoming and stick around in my life anyway. I spent too long considering things like my “brand” and “direction” and this kept me from making progress on my outline. That’s enough apologetic preamble. Here are my recent favorite books. Skip to the picture for the essay.

Motherhood by Shelia Heti. I took pictures of a dozen pages on my phone while I read this book. I sent them to friends and read through them again after I had finished the book and returned it to the library. I’m still thinking about this book and the narrator’s relationship to the question “should I have children?” Since I’m 34, I found her thought process to be deeply relatable, and it was a relief to see the same hesitations I feel many women experience articulated better over 300 pages than we can do in the 30 seconds we typically have to answer the question “do you want children?” As I gradually age through my childbearing years, the question of whether or not to have children becomes about much more than raising babies into independent beings. “Do you want children?” often sounds eerily similar to “Are you self-preserving?” when you consider the ways in which a child alters your identity, your relationships, and your future. When I consider this question on a good day, these ideas gather into something coherent and beautiful, like imagining a new beginning. On bad days, it can lead to debilitating stillness and the sense that not having children means I never made a choice—only lingered in a state of non-choosing, even if it is my choice to live out my days childfree. Here is a passage from the book:

“Just as a man might rid himself of all entitlement, violence, and need to dominate, could I eliminate from myself my desire to gossip, my petty interest in other lives—especially the darkest parts of the lives of all my female friends—and instead take responsibility for my actions and words, having decided that I won’t ever meet a future with children, and all the joys and gratifications of that? To make myself over—use my brain and be unrelenting—and pull myself out of my cloud, rather than remain in it like someone prepares to mould her morality in such a way that its highest purpose is to secure a good life for her child—with all the lies the body tells the mind, and all the tricks it plays. To make sure my body plays no more tricks, and for nothing to be said by me that isn’t true. To become like that, I will have to work harder, ensure and cause pain—not masochistically torture myself or dwell on my failures or brood miserably over a future that might not come, but will the future I most want. I’ll have to remove my feminine self-doubt, which exists out of politeness; remove my second-guessing, that utter waste of time; work harder; think harder—all the violence I will have to do to my own softness, which has always been such a comfort! I shudder to think of how I have let myself fall into the deepest sleep, like a fairy-tale princess, wasting her life in dreams.”

I loved this book, but I have read criticisms of it that circle around the argument that it is solipsistic, existential, and selfish for a woman to spend 300 pages on motherhood without being an actual mother. Criticisms like these coexisting only paragraphs after the author describes her own labor and early days of motherhood trigger my bullshit radar. Does this critique meet the work on the terms it clearly presents, or does it use the work as a launching point to wax upon the mother’s role in a thankless and demanding endurance test, something only a mother has the authority to understand? If you read the book, please help me decide.

Cheap Therapist Says You’re Insane by Parker Young. This collection of short fictions is entertaining, unsettling, and genuinely funny in a way I wish more writers understood. It is excellent fun and reading, yes, should still be fun.

When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamín Labatut. I read this book in 2 sittings: on a flight to Seattle and then at a coffee shop in Seattle while drinking a latte. That’s all it took. It’s beautiful, questioning, and timely. For anyone interested in scientific progress and the Pandora’s Box that opens wide with every groundbreaking innovation.

The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante. When I finished Labatut in Seattle, I realized had nothing else to read on my flight home, plus a library book I couldn’t easily ditch for the luggage space. I walked to Left Bank and spent an hour pawing around the shelves, paging through Alexis Shotwell, Paolo Virno and Jillian Weise volumes, zines on prison strikes and insurrection anarchy, but eventually gravitated back to the fiction shelves. I love material about secrets, about calculating women, and about the blurry ethical decisions that reveal themselves when loyalty and autonomy collide. We have always hidden things from each other. People keep secrets in relationships where full disclosure is supported without judgement, and in relationships where it is demanded without the benefit of exercising a nuanced perspective. This book explores how relational and family deception is interpreted and practiced by a girl growing into her sexuality and adult identity. Hell yeah. It’s astute and compelling and honest without a sliver of Ferrante’s moral superiority. I developed a deep appreciation and admiration for Ferrante’s technical and creative abilities after this read. In particular, the language undergoes subtle changes as the narrator gains wisdom and the limits of her world expand, so the beginning and end chapters hardly seem to be written by the same author. Exceedingly graceful writing.

Woman With Hat by Lucy K. Shaw. Much of this book is about friendship—the good kind, the honest and vulnerable kind. Shaw pulls directly from her life and her creative relationships for this book, so it reads like an account of her year and interests, with some fictional flourishes. The section on Lady Windmere’s Fan, in which the author and her close friends act out part of an Oscar Wilde play after dinner, is sweet and disarming. The play is copied directly from the original, so the reader is effectively reading the Oscar Wilde version (you can find it on Project Gutenburg) transplanted into a diaristic account of a recent summer evening. I admire what Shaw does to this section, that instead of reading a play I personally had no previous interest in, she sets it up so the reader visualizes the group of friends making a memorable evening out of this sort of dated script. It’s a clever framing device, a sweet story, and a tender rendering of creative friendships.

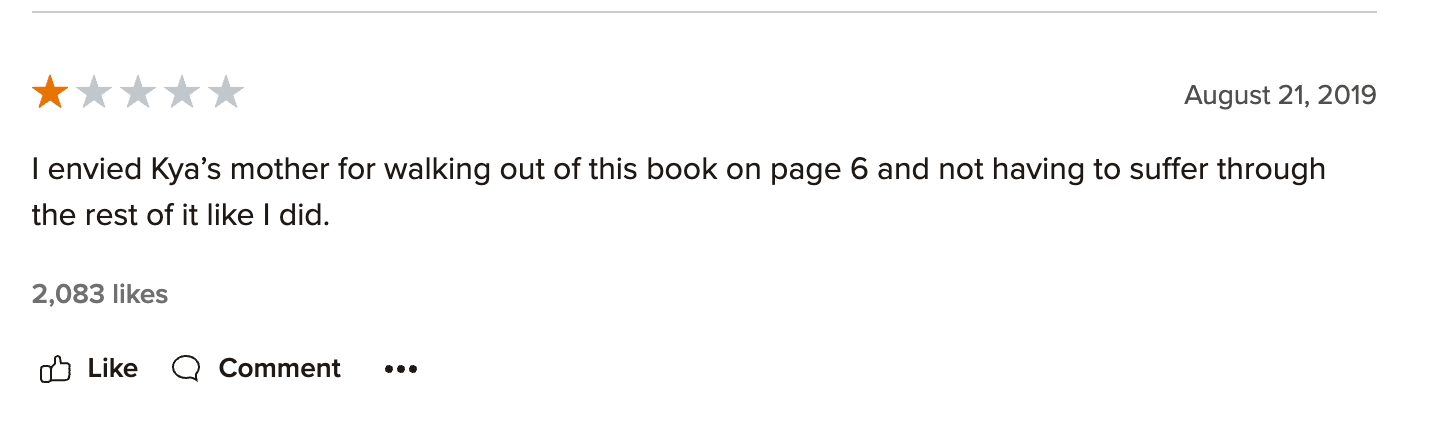

Not all reading this year has been this good. Last year, I had a stack of books to donate. I packed them in a box and took them to the bookstore with the yellow storefront and browsed the tall stacks while I had my donation evaluated. I took the store credit over the cash and brought a stack to the counter. I asked the manager for a recommendation and she looked around the displays near the counter. She pulled a copy of Where the Crawdads Sing, by Delia Owens, from the rack.

“Have you read this?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “But I know people like it.”

She placed the book on top of my stack. “You’re gonna wanna read this.” I accepted. I spent my credit and left.

Turns out, I did not want to read it. I hated this book. Or at least hated what I managed to read of it. (It came down to personal taste, so if you are someone who enjoyed it, I’m not judging you—I’m really outing myself as a pretentious reader. I am difficult to please.) Each night, when I opened the book in bed, a full cup of hot tea balanced dangerously on my chest, I groaned or cursed or sighed until J finally became so annoyed he told me to get a grip or read something else.

I don’t quit many books, but I quit this one for three primary reasons. 1) The story itself was predictable, 2) something about the dialogue repeatedly struck me as false or pandering, 3) it seemed written more for the eventual movie deal rather than for the love of art and literature. It reads like a debut novel that has been carefully extruded through the mainstream die all Big 5 publishers use to convert a mediocre manuscript into a bestseller. What came out the other end was an uncomplicated narrative carefully packaged for book clubs and movie studios. It exploited none of the actually interesting concepts it half-heartedly presented (domestication, isolation, sex, racial tensions) in favor of a safe narrative with few loose ends and not enough conflict. I felt like Owens had too much invested in the fictional character’s physical and psychic safety. This is a great quality to possess in your life—we should advocate for minimal harm and mitigate stressors on the vulnerable—but it is deeply boring in fiction and in art.

Since giving up on Where the Crawdads Sing, I’ve been thinking about when and for what reason mass public attention—a coveted and volatile phenomenon—is turned toward literary criticism—a discussion traditionally considered niche, elitist, or irrelevant to general interests. Perhaps the most democratizing example of literary criticism is Goodreads, which has become more indicative of how well a book will sell than any magazine profile or thoughtful and studied review.

Here’s the thing: nobody wants to read criticisms by someone who thinks mass produced and wildly popular art is bad. It smacks of pretension, of unfairly judging strangers and their taste. Criticizing popular novels and movies sounds makes you sound like an insufferable hipster who insists that art is better when the audience has to wade through great levels of discomfort to enjoy it.

Here’s my thing: I don’t think it’s wrong to wish that everyone who primarily enjoys mass produced media also exposed themselves to higher forms of art. I see this not as a matter of pretension, but as one of accessibility and, crucially, confidence. I’m not asking the suburban book club to critically unpack Satantango, but maybe I’m asking the suburban book club to visit the contemporary art museum without feeling out of place. Or, even better, a local art gallery. Support art that needs support—art that does not benefit so directly from wealthy institutional backing. Art that doesn’t get made into movies or a hit HBO series. I think this is why capital L Literature is falling out of fashion. Not to join The Discourse, but in the recent and controversial Paris Review interview with Shelia Heti, Lauren Oyler was asked why it seems like the young generation of writers are drawn towards fantasy, romance, and sci-fi—the “genres” collegiate writers were once were instructed to avoid in pursuit of a higher form of literary art. She responds:

“I think that for many people of the younger generations, making money signifies worth in a way that it didn’t for Gen X. Also, for younger generations, popularity signifies money, which signifies worth. This isn’t only because they’re or we’re shallow—it’s because of the deteriorating conditions of life in the U.S. and the UK, where it costs a lot of money to live barely comfortably. People want to have a nice life.”

In her next answer, Oyler describes current culture as boring and full of “droning competence”. This inevitably comes from trends, algorithms, and self-comparison exercised to damaging degrees on social media. We see what steals attention and attention is the only currency that matters anymore. Why should we hold on to ideas of creating beauty in isolation in order to touch, briefly, some vein of human truth, when we can simply perform the actions and receive much more valuable payment for unpolished ideas and flimsy convictions? The more flaccid the conviction, the more the creator seems to place unnecessary emphasis on the conditions within which the work was produced. This can be useful context in many cases, but it is also easy to erect as a defense against criticism, rendering the work itself untouchable unless critics are willing to navigate the treacherous line between the art and the creator’s identity.

When Rupi Kaur addressed her critics directly, stating “this isn’t for you,” she effectively placed herself above criticism on the basis of her identity, not the work she was producing. If the only people allowed to produce criticism we consider valid are the artist’s target audience, that isn’t criticism—that’s a customer review. Artists can rise above critique if their critics are deemed out of touch with the community that the artist intends to shape and reflect. Before you accuse me of being reactionary, consider how this technique is used to uphold belief systems that are anti-scientific, intellectually irresponsible, or to conflate criticism with literal violence. I wish to note here that not all bitching on the internet is legit criticism and most of it should be ignored to preserve ones greater cognitive powers.

In his critical overview of Ocean Vuong, Paul McAdory laments the way poetic sentimentality has gradually replaced the ugly, the hysterical, the inappropriate aspects of the human condition that are not so easily conjured with the proper pathos. I read this and immediately related it to my read of Crawdads: “Do we not grow tired, after so many rounds of this sentimental journey to the weepy, fantastical core of human experience? Might we not celebrate instead a more horizontal outlay of sincerity, mania, irony, horror, meanness, humor, etc., one in which we do not take poetic earnestness to be primary to the other affective modes but allow them to sit beside and astride one another, equally true at different moments, now in conflict, now in commerce, now merely both present and represented and felt at the same time or in succession?”

Much of this review is, perhaps, ungenerous, exposing one-liners as vapid and lacking real content, aligned with a familiar dream logic infatuation and eroticism inspires among romantics (“I’m not with you because I’m at war with everything but you”). I don’t mean to say we should be slamming writers for specific styles or tones, but I do think more book club bestsellers and Brooklyn-minted writers deserve scrutinizing beyond their MacArthur stamp of approval. Maybe too this style was a reaction against irony and hysterical realism. Painful sincerity struck a chord for a while, but I have never seen more readers and writers become defensive against criticism than when this movement was trending. Art became too personal to be criticized, and the criticism of art became conflated with criticism of individuals or their respective communities and identities. I’ve watched this dynamic on repeat in literary and public online spaces and it never seems to reach a satisfying conclusion.

On the flipside, legitimate criticism has become so elusive, so hard to identify in a sea of the rushed and incentivized criticism that pervades every corner of the internet. As soon as an item arrives at your doorstep, so too do the emails asking for your review of the product. Your opinion is their currency, and companies have found ways to incentivize 5-star reviews for sub-par products by gamifying reviews with points, tagging the reviewer in social media to drive traffic to their personal page, or just through good old fashioned relentless pestering. These efforts are swift, because once the shopping high wears off, the more likely one is to view a product critically and with balanced feedback. It is beneficial for a company to capture your opinion when the reward system in your brain is still activated, and even if your review is honest in the moment, an immediate review is too soon to discuss longevity, durability, and most other aspects of quality we have given up on in the enshitiffication era. Blocking criticism would be an easy way to continuing profiting from whatever a company is selling. But since it is illegal to block or delete honest, bad, or critical reviews, the solution has now become to flood sites with fake reviews that drown out all honest criticism. One does not need to look very far to find AI-generated fake reviews (I encourage you to dig around Amazon and input entire reviews into this ChatGPT detector. Great fun!) and nonsensical, perhaps human-written reviews that make patronizing everyday establishments seem like a peak luxury experience. Sometimes even…orgasmic?

Ok, that got a little out of hand. But seriously: how does this inescapable deluge of opinion impact art and art-making? I think about this often, in meandering fashion, without ever reaching a satisfying conclusion. But I think the biggest impact this has on art is that would-be artists find it difficult to produce work that isn’t tirelessly vetted against what other artists are producing and how their success is reflected in reviews, likes, comments, shares, bookmarks, etc., each its own type of validating engagement. Making art with the end goal that one will feel successful, validated, and popular is an extension of people-pleasing. This tends to produce art that is neither challenging nor honest, and thus contributes to the “droning competence” displayed in much media today. Art need not be bestseller material, HBO series-worthy, or even widely considered good to address the difficult and messy aspects of being human. I’d even argue that we should run towards our flaws and missteps when creating in an effort to make work that embraces discomfort.

On a concluding note, I have started pursuing critical writing and local journalism again. You can find my contributions to the Milwaukee Record here. I have thoroughly enjoyed engaging in the Milwaukee arts community and putting boots on the ground. I also have an offer to write a monthly art column for Urban Milwaukee, which I will link here once the May edition goes live.

Thanks for being here!