It is spring, finally. I feel all that latent energy come alive, triggered by a layer of warm air and the shameful snow, piled up in dirty and waning heaps in the shady parking lots behind buildings. I took Bindi on a 3 mile walk through my old neighborhood, gulping fresh air and trying remember inside my body what days in this neighborhood felt like when I was 13. My partner and I had been looking for a duplex together for months, deciding to delay owning a single family home until we knew where we wanted to live. When ours appeared equidistant between my old neighborhood and where my parents live now (apart and remarried, but near) I couldn’t help but wonder what effect moving home—and owning a home for the first time—would have on my identity. So far the results have been mixed. We moved in November, on the last nice day before the brutal Wisconsin winter rolled down from the north and settled over the region until just about last week. At the beginning, I cried a lot. Living here from 10 to 18 and again in my 30s has made me feel like the book of my life has snapped shut, the years in between then and now dissolving into pulp and ink without a trace of who I became or what I left to look for. But there are gifts: I get to be close to my family. I see my nephews more often. I have run into friends that never should have been estranged. My family relationships are rich and warm. My relationship to creative work is shaky and full of constant doubt, with goals that look so foreign compared to how I see others navigate this writing life.

“I wonder if the Internet is shifting the borders of the self, or if the self is just filtered through it.”

Bindi and I walked south but kept going all the way to the baseball park, where I let her off leash and she flew into a trot, a gallop, taking off for a small pack of robins on a muddy patch. Airborne. I tried taking a video of her running, but it was too hard to hold still. The best thing about taking a photo anyway happens in the second after it ends, when you believe you have captured the way you felt in that moment: your undeniable happiness, your lack of criticism, your absent thoughts of turning experience into work. For a second, nothing exists besides the contentment that fills your body and the dog loping underneath the budding Bradford pears.

Sometimes in those moments I think to myself, I finally got it right. And sometimes I think to myself, I could never get this right. Such is the writing life. What time is not spent writing is spent in close observation. Of the world, sure. But of ones own feelings as well. So few descriptions exist to describe sensation, but I suppose those that do exist are doomed to become cliché. It is one reason to write—to find these new ways to describe. For Amina Cain, it is a better reason to read.

A few people have recommended A Horse at Night to me since the book was published, but I initially thought it was a book on craft, which did not seem to fit the standards and limitations Dorothy Project has set for itself since its establishment. I have never flat out disliked a book from Dorothy Project, but I have found some to be too heady and too experimental for my then-current tastes. This has changed in the last year or so and I have become more accustomed to writing that pushes up on the edge of language and rejects convention with confident style, but it feels like this should have happened sooner. Studying writing at an art college meant I first learned to write by reading what my teachers considered avant-garde (in 2009). I read Amina Cain’s Indelicacy last year, the story of a woman who cleans a museum getting married to a wealthy man and moving into a new social class essentially overnight. Indelicacy, while more conventional than A Horse at Night, still rejects many of the elements I grew to consider essential in a work of fiction. But I loved the portrait of female solitude from a woman’s perspective. So much of literature is filled with women whose loneliness began once they left home, and has been cultivated, preserved, exploited, undermined, and leads inevitably to their demise worlds away from their true selves. During a time in my life when I often feel isolated from my abilities and ambitions because of such nearness to my origins, Indelicacy felt like the perfect novel.

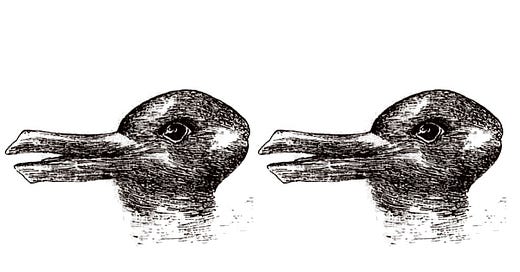

In the acknowledgements, Cain thanks a writer I studied with in college, Phyllis Moore, who once invited her class over for pancakes shaped like ducks or bunnies.

“Are you a duck or a bunny?” she asked me, pouring batter into a mold on the griddle.

“Bunny,” I answered.

“I thought I was a bunny, too,” she said. “But I have changed my mind.”

She slipped a bunny-shaped pancake onto my plate and told me to make sure to leave an offering for Edith the squirrel on her second floor balcony. At the end of the brunch she sent us all home with vintage clothes she no longer wore. I think about her question sometimes and wonder what exactly Phyllis intended by posing it to the cohort. The puzzle may have been a simple way to categorize personality, or as a challenge to understand the authentic self. Do bunnies need more approval? Are ducks more confident individuals? Have bunnies had more success in love? Is a duck more likely to live in the moment? The self is as much of an illusion as the question she posed, but I am still looking for a kind of reductive Enneagram that makes the classification black-and-white in order to understand my own position. However, like the classic illustration, it is impossible to be just one thing or another.

A Horse at Night tracks Cain’s literary sensibility more so than it follows any plot-driven story: “In the last year I’ve become fixated on the idea of authenticity. This is partly because I feel at times I have lost sight of my authentic self, and I want more than anything to come close to it again, or at least to feel close to it. For me, authenticity means that how I act and what I say and how I actually feel around others is aligned, that I am connected to myself and to another person at the same time. I want my writing to be authentic too, for every sentence to reach toward honesty and meaning.”

This is one recurring reflection in A Horse At Night: the theme of identity shifting and the nature of selfhood, particularly for those who have made a practice of turning their observations into art. I have had recent conversations with girlfriends about inner worlds and the difficulty in living domestic lives that merely preserve, never center around, our private psychology or philosophy. When daily life feels inauthentic, a sense of self can be harder to establish, and when this is threatened, writing is too. I believe this is an ultimate goal for most artists and people who self-reflect—to align their private world perfectly with their day-to-day. A Horse At Night and Indelicacy are primarily celebrations of an interior life. In many ways, it is the book I needed to read this winter as I sat with my own anxious doubts about still identifying as a writer. In Horse there is no conflict, only a philosophy that unspools page by page, one that is necessary to creativity and built upon solitude. For one to be both a contemporary human and possess a resilient selfhood that weathers unpredictable life events is to live a harmonious life. If you have succeeded in this creating balance you need to tell me how.

A Horse at Night uses other forms of art to mirror Cain’s sensibilities toward writing, reading, and observing. It is also a reflection on a specific type of female solitude. The text is peppered with references to books and music and visual art that hold some significance for the author, who uses media to weave in reflections between the self of her youth and the self of today. She writes about her travels and the books she was reading at the time, of paintings she has saved to her computer, many of women reading or dogs standing alone in fields. In this way it is possible to map out a rough sketch of Cain’s inherent solitude that has made her capable of writing a book like Horse. The prevailing sensibility is curiosity and awe at the myriad ways artists have captured the world and the inconsistent logic applied to beauty. “How can a detail be urgent and at the same time concealed? In fiction, what does that look like? And how do we bring the reader back to it? Perhaps it never leaves us, is part of the visual impression of what we’ve read, the narrative unfolding in pictures running parallel to its unfolding through events. An impression can be just as important as meaning.” Such rhetorical questions and answers are not conversations the author intends to have with her readers, but rather inquiries that have kept her in pursuit of wisdom that can be attained through a self-sequestering practice.

I wish to make a list of what affirms creative authenticity other than writing outside a near proximity to your past, because writing close to home supports the false illusion that one was never authentic at all. Walking the dog is one of them. Cooking might be another. Naming and feeding squirrels, performing rituals, inviting people over. Making and abandoning blogs. Giving titles. Writing postcards. Asking your friends about their domestic lives. Asking your friends if they identify as a duck or a bunny. Many possibilities that exist for confirming selfhood also connect us in more interesting ways, invite a vitality to our lives that later generates authentic art. Or not. I have been trying this year to write from a place of authenticity rather than from a fear of obsolescence, which means I spend more time in the world than I do at the keyboard, but I think all around this has made the practice more reliable. This requires a suspension of the illusion that one can be both authentic and insecure about direction and ideas, and that we must see the image one way or another in order to decide how to progress. I am a bunny under the chartreuse blossoms that have started to bud on our maples. I am a duck at my desk with a notebook of barely legible script. Domestic and wandering. Flighty and unflinching.

The years between then and now are not gone. The work I made still lingers in hard drives, much of it unfinished. The goals I set out to achieve look different after completion, and I wonder all the time if I would even be pursuing such questions about identity and permanence had I stayed away. I am uncomfortable living inside opposing ideas, but I am doing it anyway. I am learning to see the image both ways and I am trying not to rush the process, but trying to adopt what Cain believes is possible in a writing life:

“Write into the winter, and the summer, and the autumn, and spring. Write into the snow and flowers and wreaths and the wallpaper. Write into painting and the flame of the long candle. Write into your own mind, turning and turning it. Write into L’Homme Assis Dans Le Couloir. Write into the floor, the wide planks of the mind. Write into the circular driveway that brings your characters to you, that brings them to life.”

In this way, I suppose A Horse at Night is a book on craft in that parts of it teach you how to write while living and without laying down technical approaches or notes on prose. Write into the next daydream while walking, the next question someone asks. Write into your parents as people not parents. Write into stucco, into brick. Write into the the alley where the ghost of your childhood plays. Write into the death of friends. Write into, write on, write for, write against. Write into doubt and discomfort as often as you write into joy and surprise. Write into onion grass, write into dampness, write into photographs you forget to delete off your phone. Write into love as much as much as much as you possibly can.

In closing, I invite you to consider which one you are: Duck or Bunny. Why? When? And have you ever felt like it’s possible to be both at once? I also invite you to join me on Substack Notes. It’s a little like Twitter, but saner. I think Notes will soon be considered an alternative for the writing community. I will be on there discussing topics that aren’t quite as unhinged as those that have formed my Twitter persona, but some of it remains, I’m sure.

"I have been trying this year to write from a place of authenticity rather than from a fear of obsolescence" My favorite bit, and good job on being brave. Authenticity resonates & gives me permission to be authentic in return. Fear resonates too, but I've found when I operate from their it keeps me & the writing small. You are not small & not either your words.

(Alas I fear I am a duck, but as I loathe birds that does not please me. Or maybe it says I'm just struggling with loving myself.)